Including That Indigenous Sixth Sense In Arctic Work

INDIGENOUS

This article is a part of the series Listening to Polar Regions produced in media collaboration between JONAA and Global Geneva and published in both.

Writer: Vilborg Einarsdottir

Photographs: Vilborg Einarsdottir, Kristjan Fridriksson, Ulrik Sanimuinaq

August 2018

“Speak to us. Include us in the dialogue. We have lived in the Arctic for thousands of years; we still live in the Arctic; we are the ones who know it best,” said Okalik Eegeesiak, at the time the Chairman of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), speaking to an audience of policymakers, scientists, academics and business people at one of the early Arctic Circle Assemblies in Iceland. Sitting amongst them in the audience, I felt she was stating the obvious - but to Ms Eegeesiak it was a point that had to be made. For all the right reasons. JONAA editor, Vilborg Einarsdottir reflects on her twenty plus years as a producer on extreme arctic locations and the people whose knowledge and experience made that possible.

Much decision-making about the Arctic and its indigenous people has happened through the centuries without including the region's indigenous voices, asking for native opinion or seeking advice from those often best fit to give it. These are facts found on most history pages of the circumpolar Arctic. And, despite being a fountain of fascination and discoveries for explorers and scientists, Arctic research has to a large extent excluded the experience and wisdom of the peoples who know best this towering nature that is so much larger than man.

Looking back two decades, I find it hard to comprehend how anyone can expect to operate on any level in the Arctic without weaving together local know-how and local wisdom with whatever expertise is required for the job. In my case, ‘the job’ would simply not have happened any other way.

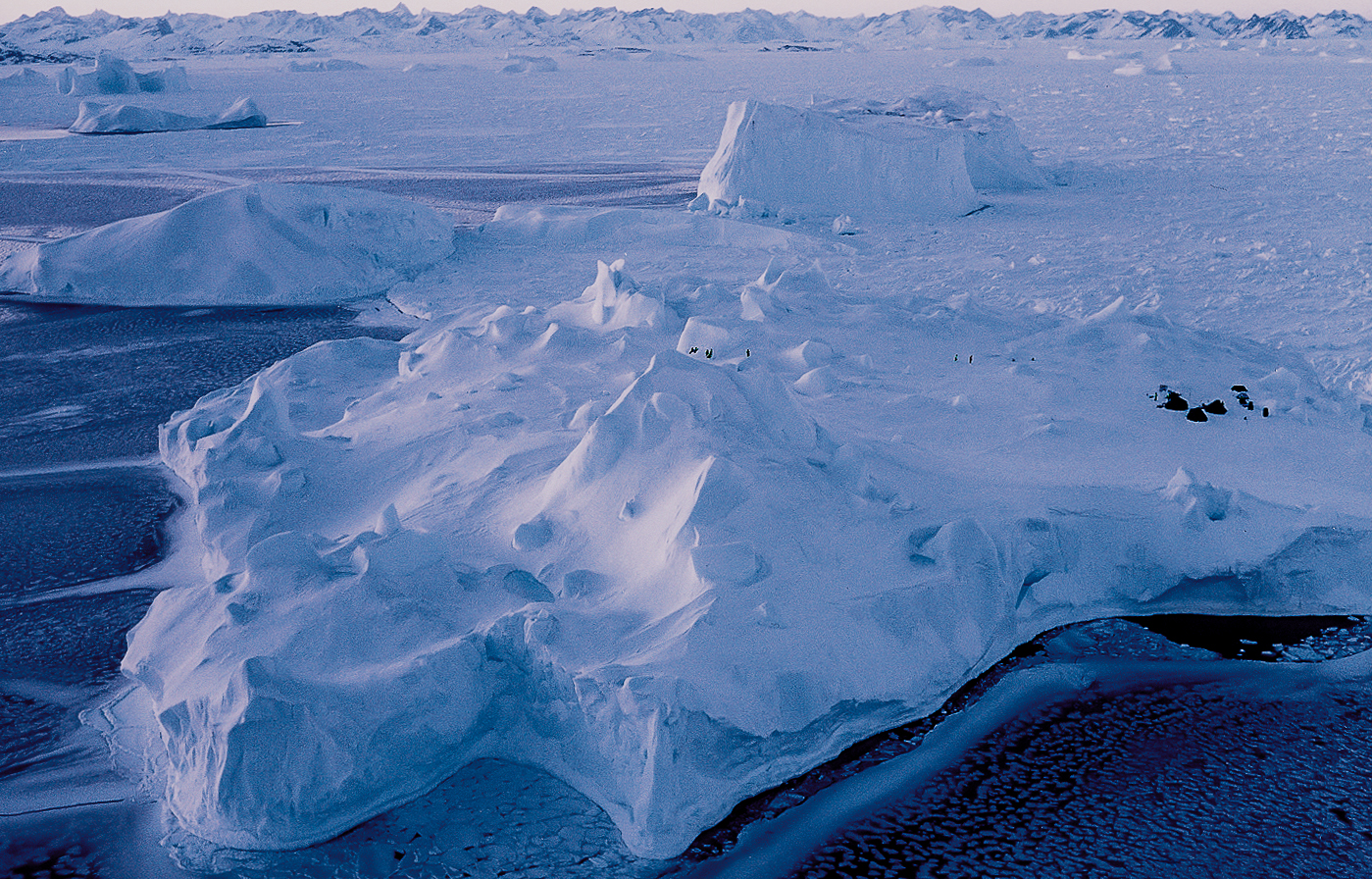

As a film, photography and media producer, I have been privileged to work since 1996 on extreme locations throughout arctic Greenland. Organising over 40 productions that have included locations such as sea-ice, pack-ice, the inland icecap, glaciers, mountains, ice floes and icebergs, ice-caves and glacier crevasses. All locations where Mother Nature sets every rule.

Not knowing and respecting her rules can quickly turn to disaster. Even fatal. The Arctic is a place where being a successful producer has less to do with brilliant callsheets, glorious “out-of-this-world” locations or the unique arctic lowlight - but everything to do with taking the time needed and using the right knowledge to properly select locations in order to make them safe for crews to work on. For that to happen, every production requires not just the right people, the right equipment and the right backup, but a firm awareness of the fact that what you need is what you bring and most importantly; that mistakes on arctic locations may have more serious consequences than mistakes made in most other places. To explain that further here are a few examples of the arctic locations I´ve worked on that offered very different safety challenges.

A brave Danish opera singer, Johan Reuter posing on an icefloe in-between giant icebergs for a Royal Opera House photoshoot by photographer Jason Bell. Out of sight on the same icefloe, armed with the rescue gear is the location & safety member of my team who first went out on that ice to establish its stability and safety.

Filming out on a fjord of frozen sea-ice, way above the Arctic circle in North-East Greenland for feature film Beyond the Pole, directed by David Williams. This shoot included various on-ice, by-icebergs and in-icy-waters locations that all posed potential safety challenges. Because of the remoteness of the location area and its tiny local community, accommodation was set up in a makeshift "container hotel", in itself a safety challenge as filming took three weeks in mid winter and freezing temperatures.

The iceberg basecamp of a Donna Karan photoshoot with photographer Peter Lindbergh. Floating 9km off shore this location needed careful preparations before anyone but the safety team set foot there. With the exception of Ulrik Sanimuinaq's lead dog who spent 3 days and nights with his owner and two others safeguarding the shoot. The reason being fresh polar bear footprints we flew over daily alongside the iceberg. But despite a production like this bringing smells and sounds alien to the environment and polar bears being curious animals at the top of the food-chain, it never climbed onto the iceberg. Had that happened this dog would have sniffed its presence long before us humans.

When it was decided to make Anningaaq, a short film directed by Jonas Cuaron, showing the "earth" side of a conversation from space in feature film Gravity, it was late winter. Almost too late. This beautiful and innocent looking location in a small frozen fjord in North-West Greenland was carefully monitored during the shoot and for good reasons. Three days after filming finished this ice had broken up and a large part of the fjord was open waters.

When getting to location by helicopter is not an option and neither are snowscooters nor dogsleds because of the terrain, well that is when a production drags and carries equipment, gear, food and props. And safety is the absolute priority. This is from a commercial shoot directed by Bram Schouw on the Greenland icecap that needed 360˚ of endless waves of ice and snow. Preparations took over a week and during the film shoot basecamp was made on the ice where everyone stayed in tents for 3 nights and traveled daily a kilometre by foot to location.

It is all about safety

In other words, it is all about safety. It is all about understanding that an extreme Arctic location represents a complicated and potentially dangerous environment that can change in an instant. An environment that you have little control over. It controls you. One needs to know the local snow and ice conditions, the weather and the cold coupled with the limitations – or opportunities – brought by the hours of existing light. One needs to rely on the essential local know-how of the environment required for bringing in crews from far away and often very different places, and to ensure that they remain creative, focused and unafraid in Arctic conditions. One also needs to know how to react to changes in these conditions should they happen. Which they do. This means having a B plan, and a C plan and a D plan - and a team that has seen it all, understands the elements of arctic nature and arctic weather and can quickly put the B, C or D plan into action.

The locations & safety team, Ulrik Sanimuinaq and Denni Reynisson (center) on top of a giant iceberg in Ilulissat in North-West Greenland. This production was for a music video to "A Beautiful Lie" by 30 seconds to Mars, directed by Jared Leto. JONAA©Kristjan Fridriksson.

Years of professional filming expertise go a long way. At the end of the day, however, the real knowledge and expertise needed can only originate from years of work and survival on the ice. It is recognizing that critical ‘sixth sense’ of reading the ice, snow and weather that comes from living in the Arctic hunting communities. This I learned in 1996 and this has been the foundation for all the productions that I have organized in the Arctic.

From the very beginning, my locations & safety team base their work on careful planning coupled with a combination of local and professional expertise. This three-man team is connected by a longtime friendship and shared experiences, respect and, most importantly, trusting each other with their lives. It is led by Kristjan Fridrikssson, an Icelandic art director/photographer turned Arctic-locations specialist. Kristjan left his post as an advertisement agency owner and commercials director to spend a year traveling, photographing and documenting ice, snow and Arctic locations in East Greenland with two native hunters. He quickly understood the realities of what was needed in terms of safety, logistics and infrastructure if one was to bring foreign productions to Greenland. Local know-how was on top of that list.

The location & safety team leader, Kristjan Fridriksson, art director and arctic photographer who 20 years back got the idea to present Greenland for international film and photography. Here in preparations with another team member on the same giant iceberg in Greenland. JONAA©Ulrik Sanimuinaq.

The navigation specialist in the locations & safety team - an outstanding hunter and incredible man, who always seems two steps ahead in knowing what to expect from arctic nature. East Greenlandic hunter Tobias Ignatiussen. JONAA©Kristjan Fridriksson

Ulrik Sanimuinaq, one of Greenland's great polar bear hunters. An exceptional individual with a unique understanding of different ice conditions and deep respect for the towering arctic nature, all its elements and all its living things. JONAA©Kristjan Fridriksson.

The other key members, the two Inuit hunters who have spent their lives on the sea ice in East Greenland, Tobias Ignatiussen and Ulrik Sanimuinaq. Each has brought his own essential local expertise to the project and this three man team is the reason that I have been able to do my pretty fascinating job as an Arctic producer for so many years. And everyone has survived!

Tobias and Ulrik are natives, members of the Ammassalimiut Inuit from Greenland’s East Coast. Anthropology defines them as the “world’s most recently discovered civilization”, an indigenous society discovered in 1884 when they consisted of only 419 individuals. Today, they are close to 4,000, living in the Ammassalik region which is made up of the main town Tasiilaq and five habited settlements, Kulusuk, Kuumiut, Sermiligaaq, Tinitequillaq and Isortoq. They speak East-Greenlandic, an Inuit language not easily understood even by the rest of the Greenlanders. This tongue has never existed in written form; it is amazing to have survived.

Tobias and Ulrik are in many ways different hunters with very different experiences but seal, of course, is the core of their hunting work. Because sealmeat is what feeds their families and their dogs, and quite often, also their neighbours, relatives or less fortunate members of their community. The hunting culture tends to be one of sharing and these two are good examples of such generosity.

Both are regarded as superior hunters and respected as such in their communities. And both have made lifetime careers rooted in the hunting culture and traditions of the Ammassalimiut heritage. Ulrik for example, learned hunting from his father at an early age, catching his first seal at the age of eight and his first polar bear at the age of eleven. His lifetime's work has been spent on the polar pack ice off Greenland's east coast, hunting to bring food to his family table, to feed his dogs and to support his children. He is one of Greenland's big polar bear hunters, who stopped counting a few years back when he passed the 70 polar bear mark. He still kayaks in the traditional way to hunt narwhal with his spear and his wife Ane is renowned in the region for exceptional skills in working skins, making long lasting waterproof and warm kamiks and is one of the few left with the skill to make a sealskin kayak.

Ulrik Sanimuinaq camping for the night on frozen sea. In his lifetime as a hunter he has seen great changes affect his life and ways of living. Changes brought about by humans with anti seal hunting campaigns and policy decisions - and changes brought about by nature through climate changes and loss of sea ice. JONAA©Kristjan Fridriksson

Ulrik has no count of the seals he has caught in his life, but each and every one has been used to the fullest, the meat and fat eaten, the intestines and bones used for the dogs and of course the skins, at one time the most valuable by-product of seal hunting, carefully cleaned and dried for clothes, ornaments or kamiks. In other words, every part of the animal is used. Needless to say Ulrik's household like those of other hunters in Greenland has suffered greatly through past decades from the devastating effects of international anti-sealing campaigns and the EU ban on seal products implemented in 2010 - because clauses with exceptions for indigenous and ethical hunting simply do not hold. No one reads the fine print. So there is the loss of income, the emotional pain and hurt pride in addition to the thinning ice, loss of sea-ice meaning loss of hunting grounds and general effects of climate change that all combine to greatly affect the existence of Inuit hunters like the two on my team. But that is an issue for another article. Back to that sixth sense.

Both Tobias and Ulrik will tell you the type, gender, size and probable age of a seal which to you may be a tiny black dot in the ocean hundreds of metres away. Or tell you to look “there” pointing to a totally calm spot on the surface of the sea, seconds before that majestic whale surfaces. Or figure out from polar-bear footprints in the snow, how long it is since it passed by, the weight of the animal, whether it is male or female, young or old. And should the polar bear be caught, their assumptions will be proven right. They can also observe the ice and read from the surface how thick it is, how old it is and most importantly - how safe it is.

One unforgettable moment for me was returning to an ice-covered bay after a night of heavy rainfall. The rain had cleared roughly a metre of the newly fallen snow that we had travelled across on snow scooters and dogsleds the previous day. Ulrik, who was in the lead as always when we put people on ice, had suddenly summoned everyone to stop. He looked in silence for some minutes over the even field of unbroken snow before us and then led the group zigzagging over the wide fjord and onto location. Standing in the same spot the next day I saw why. The rain had exposed an alarming, partly-open 150 metre long crack criss-crossing the ice. It was a crack avoided the previous day because Ulrik's instincts and experience allowed him to read the ice beneath all the snow and steer a group of 23 people out of harm’s way. This is that sixth sense.

Ulrik on the frozen fjord mentioned in the text. JONAA©Kristjan Fridriksson

Closing the compass and relying on instincts

On another occasion, we were sailing 12 people in three open boats through heavy pack-ice, heading from location back to Tasiilaq. Midway through the expected two-hour trip we were hit in an instant by fog so solid and dense that passing icebergs and icefloes only became visible when they scraped the side of the boat, near enough to touch. In retrospect, there was something magical to that vision. But at the time it was simply terrifying.

What brought us safely to shore was Tobias’s experience, navigational skills and understanding of the ice. In such conditions, he closes the compass and relies on his instincts. Steering the first boat, he worked it through the pack-ice like an icebreaker, inching through it and making a trail for the other two to follow. What began as yet another beautiful boat trip passing the occasional iceberg turned into a silent cruise through seemingly solid ice. After four hours of careful navigation in a fog just as black as before, we suddenly found ourselves by the pier in Tasiilaq. That sixth sense again. It has kept these hunters alive, and in such situations, it has kept me and my people safe.

Tobias and Ulrik simply read ice and snow like the rest of us read a book. Their respect for Arctic nature and all its living things is the core of how they live and work. The Arctic is their home. They understand the harmony and balance that has to be kept. It is the core of how they think. They not only understand the elements of the Arctic, they feel them. They sense changes, sense danger and make the right decisions. Such knowledge, wisdom and understanding of often fast changing conditions is precisely the point made by Ms Eegeesiak in her Arctic Circle Assembly speech. Wisdom originating from life experiences and lessons learned and passed down through generations of living in the Arctic is wisdom and experience too important to ignore. ▢

Vilborg Einarsdottir is the Editor-in-Chief of JONAA, the Journal of the North Atlantic & Arctic and a JONAA partner & founder. Formally a journalist for 12 years at Morgunblaðið in Iceland, she has worked since 1996 as a specialised producer of film, photography and media productions on extreme locations in Arctic Greenland and as a cultural producer in the Nordic-Arctic region. She is an awarded film and documentary scriptwriter and editor of photography books from the Arctic.