Arctic Aliens: Homo Sapiens, The Greatest Invader Of Them All

SCIENCE / ARCTIC TRAVEL

Writers: Jesamine Bartlett & Kristine Bakke Westergaard // Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

Photographs: Justin Levesque, Helge M. Markusson, Vilborg Einarsdottir.

Graphics: Kristine Bakke Westergaard & Jesamine Bartlett

October 2020

The Arctic is the fastest warming region on Earth: ice is melting faster than ever, exposing land that is ripe for colonisation and occupation by both native and invading species.

But it is not only flora and fauna that are travelling north: so are we. Homo sapiens, the greatest invaders of them all.

Researchers Jesamine Bartlett and Kristine Bakke Westergaard explain how whilst visiting the polar regions can be a life-changing positive experience for the visitor - it can easily create dangers for Arctic environment. Often from unintentional transport of alien species, like the average 3,9 seeds found on the footwear of visitors arriving at Longyearbyen airport in Svalbard. But cleaning one’s hiking boots is only one of many issues to consider before setting foot on Arctic terrain.

Human activity in the Arctic reaches record levels

Global biodiversity is under attack, especially from alien species, climate change, and changes in land use. And where these threats converge – as they do in the Arctic – the consequences for local ecosystems will be hardest felt.

Human activity in the polar regions has been at record levels in the past leading up to 2020, with over 45.000 people visiting Antarctica in 2017 and 2018. At the same time tourism became a pillar for local economies in remote Arctic communities such as Longyearbyen in Svalbard and settlements across Greenland. Svalbard in particular saw an unprecedented rise in tourism, with over 73.000 visitors arriving in 2018.

In comparison it means that 30.000 more tourists to one island in the Arctic than the number of tourists that visited the whole of the Antarctic continent during the same year.

In 2018, most visitors to Svalbard arrived on cruise ships, in all some 46.000 individuals. But by the end of September 2019, some 81.000 people had arrived to Svalbard’s Longyearbyen airport. And right up to Covid-19 bringing tourism to a worldwide standstill, there were no signs of any there is no sign of these numbers slowing, with investment in the town geared to tourists, and an ever-increasing fleet of expedition cruise ships and companies.

Prior to Covid-19, investments in Longyearbyen, Svalbard were largely geared to tourists, and an ever-increasing fleet of expedition cruise ships and companies. JONAA©Helge M. Markussen

Whilst many of us visiting these remote places take care to ensure we “leave no trace”, we do not account for what we unwittingly transport. An examination of the footwear of 259 air travellers coming through Longyearbyen airport found an average of 3.9 seeds on each person. This amounts to 270.000 seeds imported into Svalbard every year, a quarter of which are able to germinate under conditions found in Svalbard. In Barentsburg, the paths walked by visitors each summer are flanked by weeds scattered by humans. In a landscape that is otherwise stark and barren, the verges of paths are verdant green.

Although the Svalbard Environmental Act prohibits the intentional introduction of alien species to the region, there is currently little regulation on the imports of plants and fodder into Svalbard. This, in addition to increasing human activities, heightens the risk of unintentional introductions, and is now cause for growing concern amongst decision-makers.

Whilst ensuring we “leave no trace” when visiting the Arctic, we do not account for what we unwittingly transport. JONAA©Vilborg Einarsdottir

Hitch-hikers on imported plants

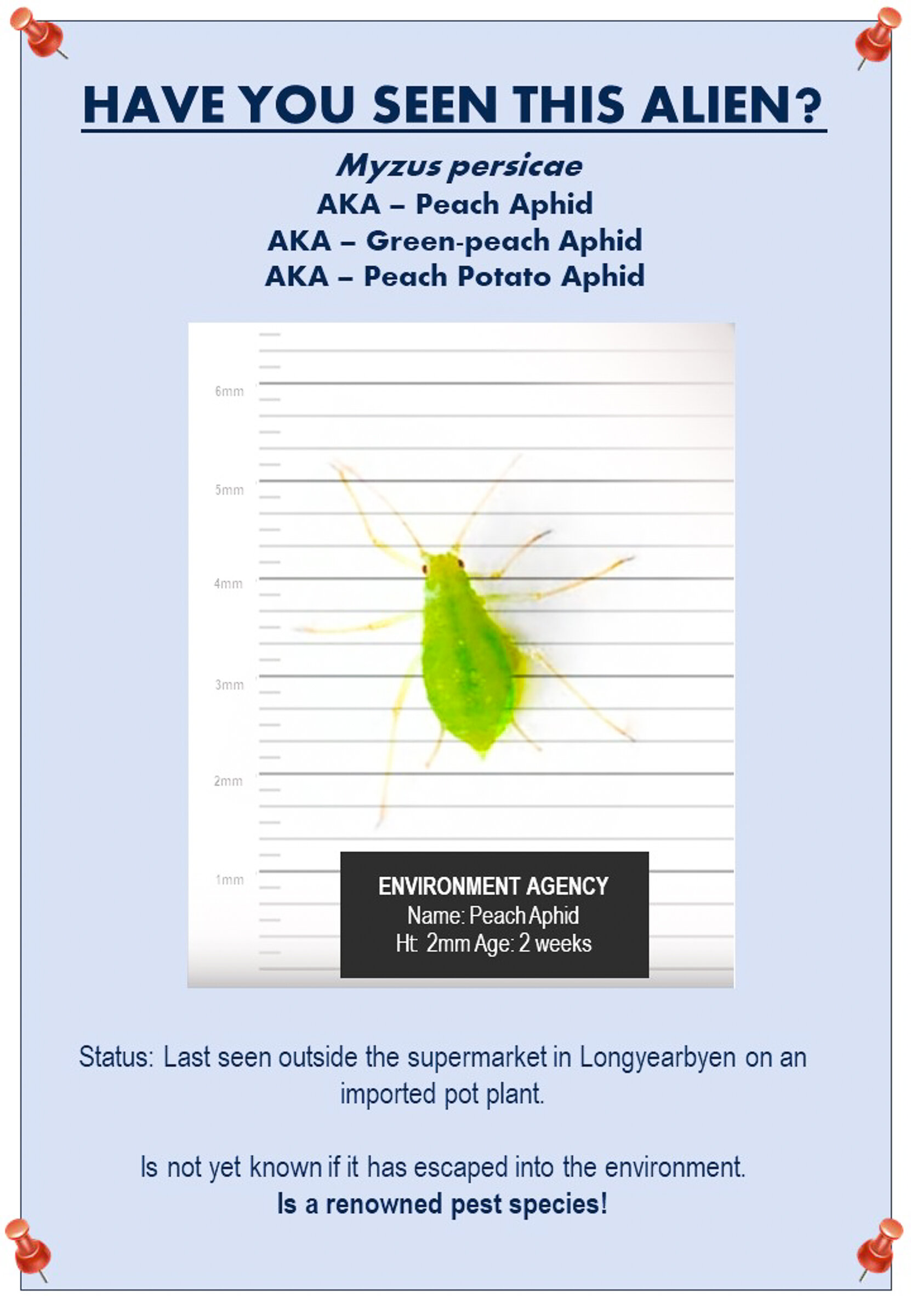

Ornamental plants are imported to Longyearbyen’s grocery store for local residents, yet whilst the plants themselves could not survive life outside of someone’s living room, hitch-hikers on them may be able to.

A survey of imported pot plants that were outside the only supermarket in Svalbard during summer 2018, when temperatures are above freezing, found the green-peach aphid Myzus persicae to be happily occupying three different ornamental plants. This aphid is a known pest species, with a cold-tolerance physiology that may just allow it to colonise the area. Whether or not it has managed to do so remains to be seen.

What is an Alien Species?

The term "alien species" includes all species that have been propagated outside their natural range by means of human activity. This also includes subspecies, local varieties of species, and man-made varieties such as livestock breeds and cultivated plants. The spread is not limited to national borders, but can also include spreading within the country, such as the launching of pike in waterways where the species could not spread to itself.

Alien species harm local nature in several ways: For example, new species coming in can change the environment and outperform indigenous species. This is especially critical if it affects species that are already threatened for other reasons. Alien species can also bring their own stowaways, such as parasites and new diseases. They can also interfere with indigenous species and in some cases reduce overall genetic diversity.

It can be hard to define an alien organism, especially when this applies to variants of a species. In order to best map and monitor alien species, we need a good overview of the natural diversity of Norway to begin with and the history of a species: For example, how do we treat the return of wild boar to Norway after a period of national extinction? Or the roe deer that first wandered into the country in the 20th century?

Whatever the reason for the spread of a new species, it is important for the management of nature that they are monitored, and that we investigate the effect on indigenous nature. Many species will be impossible to remove from ecosystems once they have established themselves. So the most effective measures are those of early detection and mapping of the spread for continued monitoring and management.

Definition from NINA, the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

WANTED:

Non-native plants left behind

Imports to Svalbard have occurred now for decades, most notably, to the settlements of Barentsburg and Pyramiden which have previously held significant communities of 1000 people each. Both towns were deliberately planted with imported grasses to “green” the communal areas and make residents feel more at home. Though the people may have left over the years, non-native plants like Deschampsia cespitosa still remain.

Not only did the communities import plants for decoration, but they also imported farm animals to support the human population. The animals themselves were kept in stables, but their dung, bedding, and waste fodder were all thrown outside, creating mounds of fertile soils that also contained seeds.

Most diverse vegetation around old farms

Now, one can find some of the most diverse and lush vegetation in all of Svalbard in and around these old farms. There, Barbarea vulgaris, winter cress, reaches over a metre in height, flowers, and reproduces. Taraxacum officinale, the common dandelion, is so abundant in places that there are too many plants to count and the landscape is yellow with flowers in summer. In the main town of Longyearbyen, a similar planting scheme in the past is why lawns of Festuca rubra can now be found lining some roads.

Whilst these farms are now abandoned and the pigs and cows long gone, the problem of animal husbandry on Svalbard has not gone away. With the rise in tourism has come a rise in dog yards. Year-round dog sledding through the beautiful valleys in and around Adventdalen, near Longyearbyen, has become a main activity choice for visitors to the area. A new dog yard has now been established in Barentsburg, and another is likely in Pyramiden in the future. In 2019, approximately 500 dogs are owned by the four main sledding companies, and as many as 20 new puppies are born in the larger dog yards each year. The dogs, like the farm animals, fertilise adjacent ground and unusually green vegetation surrounds the kennels as a consequence. Like the old farms, dog yards use hay and straw rich in seeds to bed the animals through the cold.

A group of international travellers visiting the abandoned Russian town of Pyramiden on Svalbard. JONAA©Justin Levesque

Strong links between animal husbandry and alien plant species

Recent surveys of invasive plant species in the Longyearbyen and Adventdalen area found strong correlations between animal husbandry and alien plant species. We do not yet know what invertebrates or microbes may be imported too, but for now the impact from plants and nutrients alone is evident. Alien species, both plants and animals, tend to outcompete native species for everything from space to nutrients, and even sunlight. Invasions are one of the biggest threats to global biodiversity, after all, and now Svalbard must learn this lesson, just like the rest of the world.

As climate change makes the harsh winters and cool summers of the Arctic increasingly favourable to any hitchhiking species, as the retreat of ice opens up more soils for colonisation - and as human activities fertilise the barren ground, we can no longer turn a blind eye to the issue of alien species in even the most inhospitable areas of our planet. If we are to maintain the Arctic as a place that is world-renowned for its unique ecology and landscapes, then actions must be taken to protect it. Whilst long-term societal changes are needed to turn the tide of climate change, political decisions that will increase biosecurity and personal responsibility in Svalbard can be taken with comparative ease and rapidity. If you choose to travel north, check your own clothes and equipment for seeds and stowaways, and visit www.stoparcticaliens.com for more information on what you can do to ensure that your footprints are just that.

Visiting the polar regions can be a life-changing experience, and teach visitors a lot about the planet, the environment, and why it is worth protecting. But remember that in a world where we cannot survive without significant protection from the elements, we are aliens too, and where we go, other aliens tend to follow.▢

One should not only tread carefully when visiting anywhere in the Arctic - but be mindful of what may be coming along. JONAA©Vilborg Einarsdottir

Kristine Bakke Westergaard is a researcher in the Terrestrial biodiversity department at NINA. Her research interests areo historical and contemporary species dispersal and plant conservation and her work spans the fields of biosystematics, plant geography, conservation genetics and genomics, landscape genetics, vegetation ecology, and floristics.

Jesamine Bartlett is a a polar and alpine ecologist who studies invasive species in the Arctic and Antarctic. She is currently a researcher at NINA, formerly with the University of Birmingham and the British Antarctic Survey. She is a multi-disciplined field ecologist, with interests in how the invasive species and anthropogenic change can influence ecosystems across trophic levels, from soils to landscapes via the biology in between.