Unlike Antarctica, There Is No Arctic Treaty

POLICY / POLAR LAW

This article is a part of the series Listening to Polar Regions produced in media collaboration between JONAA and Global Geneva and published in both.

Writer: Charles H. Norchi

Photographs: Ragnar Axelsson, Björn Gislason, Kristjan Fridriksson

June 2018

The snow is receding from the hills of Akureyri, along with the darkness and clicks of crampons on the ice-covered sidewalks. The northern lights have faded. Greenery, tourists and harbour whales now re-appear.

Professor of law, Charles H. Norchi, writes from this second largest city of Iceland, home to Arctic Council working groups on the Marine Environment (PAME), and Flora and Fauna (CAFF); the Stefánsson Arctic Institute named for the Icelandic-Canadian explorer Vilhjálmur Stefánsson; the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) and other specialized organizations, all headquartered in one building. The University of Akureyri occupies the adjacent building and offers a degree in Polar Law which compares polar-opposite legal systems that share a common condition — the cryosphere: water in solid form.

The cryosphere has long been the driver of polar activity exploration, hunting, fishing, research, shipping, drilling, mining, conservation, livelihoods, geopolitics — and the law intended to regulate and facilitate those activities.

Science underpins exploration

The Akureyri research institute named after Stefánsson is a reminder that science underpins exploration. In Antarctica, the 1840 expedition of British Naval officer and scientist James Clark Ross identified the enormous ice barrier now known as the Ross Ice Shelf. In 1881 Adolphus Greely commanded an Arctic expedition for the first International Polar Year to establish a series of meteorological-observation stations and became the first president of the Explorers Club.

Akureyri, North Iceland. JONAA©Björn Gíslason

Physician and ethnographer Frederick Albert Cook claimed to have reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908, a year before fellow Explorers Club member Robert Peary. Cook was made President of the Club and then kicked out when his polar claim was rejected by the University of Copenhagen. In 1909 Robert Peary and Matthew Henson used Inuit indigenous knowledge in their attempt to reach the North Pole. The Norwegian Roald Amundsen (another Explorers Club member) first sailed the Northwest Passage.

The objective of the 1910-1913 British Antarctic Expedition led by Robert Falcon Scott was to reach the South Pole for the British Empire and to advance science. Scott and his men perished and Amundsen reached the South Pole first. The 1914-1917 Trans-Antarctica Expedition of Ernest Shackleton on the vessel Endurance ended in near disaster. After leaving most of his crew on Elephant Island, Shackleton with four men set out in a row/sail boat over 1,000 miles of open sea, returning on a Chilean steamboat to rescue his stranded crew three months later. In the public imagination, the polar regions were associated with exploration, adventure and ice.

The town of Akureyri, population 18,000, is a short sail to the island of Grímsey, population 100. Latitude 66° 33 ́ N runs through north Grímsey, thus securing Iceland's position as an Arctic state. And Akureyri is Iceland's gateway to the Arctic.

Science over political and territorial competition

Antarctica was terra nullius under the international law of the period. Hence territory was claimed and national flags planted. But as science became paramount, competition receded, states cooperated and this transformed law in the Antarctic.

During the 1957 International Geophysical Year, inter-state cooperation enabled 12 nations to establish more than 60 research stations on the continent. This became institutionalized with the Antarctic Treaty signed at Washington on December 1, 1959. The treaty sets geopolitics and territorial claims aside, demilitarizes the continent and facilitates scientific cooperation. There are now 50 state-parties with a Secretariat in Buenos Aires, Argentina. During the last International Polar Year of 2007-2009, researchers cooperated in both polar regions during summer and winter.

In the Antarctic, science drove cooperation and nation-state claims were “frozen”. But geopolitics still permeates the Arctic, albeit less intensively than during the Cold War. Russia operates many High Arctic vessels-ships and submarines – including a fleet of nuclear powered icebreakers. President Vladimir Putin has indicated an urgent need for Russia to secure strategic, economic, scientific and defence interests in the Arctic.

Russia’s Northern Fleet Joint Strategic Command has Arctic responsibility and has increased military flights near Canadian and Danish airspace. NATO’s Arctic member states – the United States, Canada, Denmark, Norway and Iceland – have reinforced defence capabilities. Thule Air Base in northwest Greenland is the northernmost American military base.The former air base in Iceland is now the international airport at Keflavik.

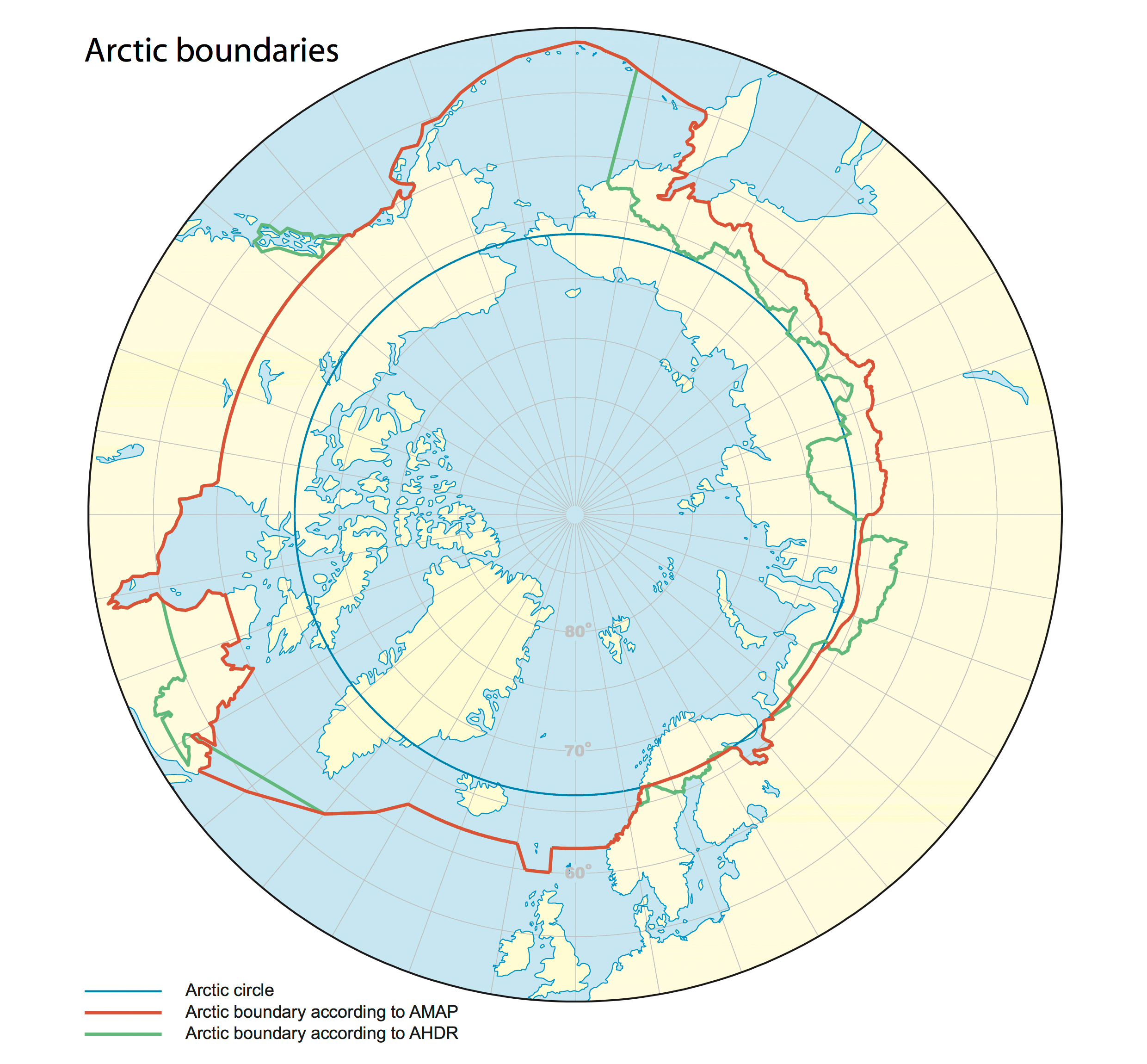

Eight Arctic circle states but no Arctic treaty

The Arctic comprises the world’s fourth largest ocean and eight Arctic Circle states: Russia, Canada, Denmark by virtue of Greenland, Norway, Sweden, United States, Finland and Iceland. Most activities are subject to the law of the sea and maritime law. But unlike Antarctica, there is no Arctic treaty.

Boundaries circling the Arctic Ocean and the North Pole. Map compiled by Winfried K. Dallmann / Norwegian Polar Institute. Published with permission from the Arctic Council.

States mostly assert claims through institutions established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) or by means of diplomacy, propaganda and force. Russia has asserted claims to nearly 1.2 million square kilometres of territory, including the North Pole in a submission to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). In 2007 a Russian expedition planted the country’s flag 4200m underwater, directly below the North Pole.

Despite occasional tensions, the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental organization established in 1996, encourages cooperation. Comprising governments, NGOs and indigenous communities, it is a forum that assures science is at the centre of decision-making on matters such as the environment, navigation, fisheries, economic development and indigenous peoples. The Council Secretariat is in Tromsø, Norway and is currently chaired by Finland under the rotational system.

Separate treaties and agreements relating to the northern polar region including the 2011 Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement, the 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic, and the 2017 Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation and the Polar Code pertaining to navigation which is applicable in both polar regions. A new treaty for the conservation of marine life is being considered by the United Nations and could apply to the Central Arctic Ocean.

Dancing for access - and control

What has been termed the “scramble for the Arctic” is in reality a dance of access and control. The dance implicates the environment, navigation (Is the North West Passage Canadian or international waters?), oil and gas, commercial fishing, security, and emerging business ventures. It affects indigenous peoples and the resources they steward. And access is sought by the so-called “near Arctic States” – China, India, Korea and Singapore, all of which would benefit from Arctic shipping routes that are shorter than the traditional South China Sea, Suez and Panama routes.

And at the centre of Arctic relations is this land of fire and ice –as Iceland punching above its weight. The Althingi, Iceland’s parliament since 930, has identified as priorities the Arctic Council, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, fisheries, climate change, sustainable use of natural resources, security, commerce and collaboration with the Faroe Islands and Greenland with special attention to indigenous peoples. Akureyri is now a magnet for many working on theses about High North issues. In 2019 Iceland will assume the chair of the Arctic Council and thereby influence answers to the question of who will get what, how and why in the Arctic. This is the regional dance. But science, especially knowledge of cryospheric change, will condition the weal and woe of polar life. The dance is far from over. ▢

Charles H. Norchi is Co-Chair of the Arctic Futures Institute (USA) and the Benjamin Thompson Professor of Law, University of Maine School of Law. He is currently a Fulbright-Ministry of Foreign Affairs Arctic Scholar in Iceland. A contributing editor of Global Geneva and a member of the JONAA advisory board.